Higgs Boson: From Concept to Reality

The story of the Higgs boson is instructive, since it demonstrates rather clearly the way that experiment informs theory, and conversely the way that theory guides experiment. It is very unusual in science for a prediction to be made so long before its experimental verification. In 1964 particle accelerators and detectors were still rather primitive, and computing was in its infancy: theorists worked mostly with pencil and paper, and experimentalists could only dream of a machine capable of exploring electroweak symmetry breaking.

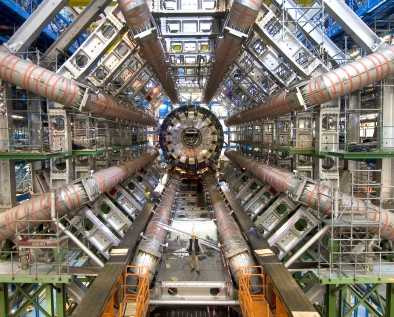

The discovery of a Higgs boson at CERN in 2012 was a fantastic technological and sociological achievement. But above all it was a remarkable demonstration of the predictive power of the human mind.

More information about Peter and his boson may be found on the University of Edinburgh Peter Higgs web pages.

The long and winding road to the Higgs boson

1928

Heisenberg uses spontaneous symmetry breaking to describe ferromagnetism.

1947

Bogoliubov describes superfluidity in terms of the spontaneous symmetry breaking of a global symmetry.

1954

Nonabelian gauge theories are constructed (Yang and Mills): the gauge bosons are necessarily massless.

1957

Superconductivity is also explained in terms of spontaneous symmetry breaking (Bardeen, Cooper, Schrieffer).

1957

Parity violation is discovered, showing that the weak interaction is chiral (Yang, Lee and Wu).

1960

Spontaneous symmetry breaking of chiral symmetry in a quantum field theory explains the observed spectrum of nucleons and pions (Nambu and Jona-Lasinio): a composite scalar field with a vacuum expectation value gives mass to the nucleon.

1961

Glashow writes down an electroweak gauge theory, but the gauge bosons, leptons and quarks are massless.

1962

Goldstone proves that in a Lorentz invariant quantum field theory spontaneous symmetry breaking of a global symmetry through the generation of a vacuum expectation value for a scalar field necessarily gives rise to massless particles: Goldstone bosons.

1963

Anderson suggests that "the Goldstone zero mass difficulty is not a serious one, because we can probably cancel it off against an equal Yang-Mills zero-mass problem".

1964

Brout, Englert and Higgs show that in a Lorentz invariant gauge theory coupled to a scalar field, spontaneous symmetry breaking generates a mass for the gauge bosons, with no massless particles: the Goldstone bosons are 'eaten' by the gauge field. Higgs points out that "an essential feature of this theory is the prediction of incomplete multiplets of scalar and vector bosons".

1967

Weinberg shows that lepton and quark masses also arise through spontaneous symmetry breaking of electroweak gauge symmetry.

1971

The Glashow-Weinberg-Salam electroweak theory is shown to be renormalizable by ‘t Hooft and Veltman.

1974

Charmonium is discovered, simultaneously at Stanford and Brookhaven, at 3GeV (Richter and Ting).

1975

The first 'phenomenological profile' of the Higgs boson (Ellis, Gaillard and Nanopoulos) concludes that "people performing experiments vulnerable to the Higgs boson should know how it may turn up".

1983

The W and Z bosons of electroweak theory are discovered at the CERN SPS, at 80 GeV and 91 GeV (Rubbia).

1989

The search for the Higgs begins in earnest, with the publication of the 'Higgs Hunter’s Guide' (Gunion, Haber, Kane and Dawson), and the start of LEP at CERN.

1995

The top quark is discovered at the Fermilab Tevatron, at 175 GeV.

2001

LEP sets a lower bound of 114 GeV on the Higgs boson mass, virtual corrections preferring masses below 200 GeV. LEP is shut down to allow construction of the CERN LHC.

2008

First beams circulate in the LHC ring.

2011

Higgs masses between 147 GeV and 180 GeV are excluded by the Tevatron.

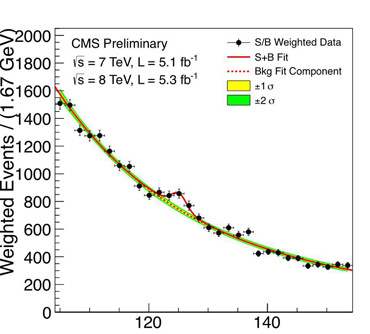

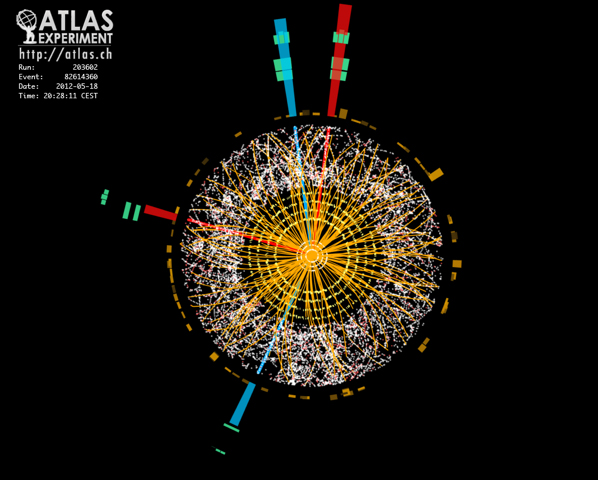

2012

A candidate for a Higgs boson of mass 125 GeV is discovered at the LHC by both experiments ATLAS and CMS.

2013

Englert and Higgs are awarded the Nobel prize, 49 years after making their prediction.

Find us on social media:

TwitterFacebookYouTube